See other cases

Sometimes we can also look for zebras… in the pancreas!

A 66-year-old patient, known to have nephrectomy 16 years ago for Grawitz tumor, with impaired glucose tolerance, undergoes investigations for a pancreatic lesion discovered incidentally, being asymptomatic.

Clinical: asymptomatic.

Biological: isolated elevated values of GGT, dyslipidemia, inflammatory syndrome (VSH x 3 N); CRP, tumor markers (CEA, CA 19-9), blood count – within normal limits.

Abdominal-pelvic CT with contrast revealed in the cephalic pancreatic region, in the vicinity of the superior mesenteric vein, without compressive effect on it, a clearly contoured native isodense formation, with intense contrast uptake, with discrete washout in the venous and late phase. No tumor recurrence in the right renal lobe after nephrectomy, no other signs of metastatic disease

Chromogranin A, pancreatic polypeptide and 5HIAA are dosed – within normal limits.

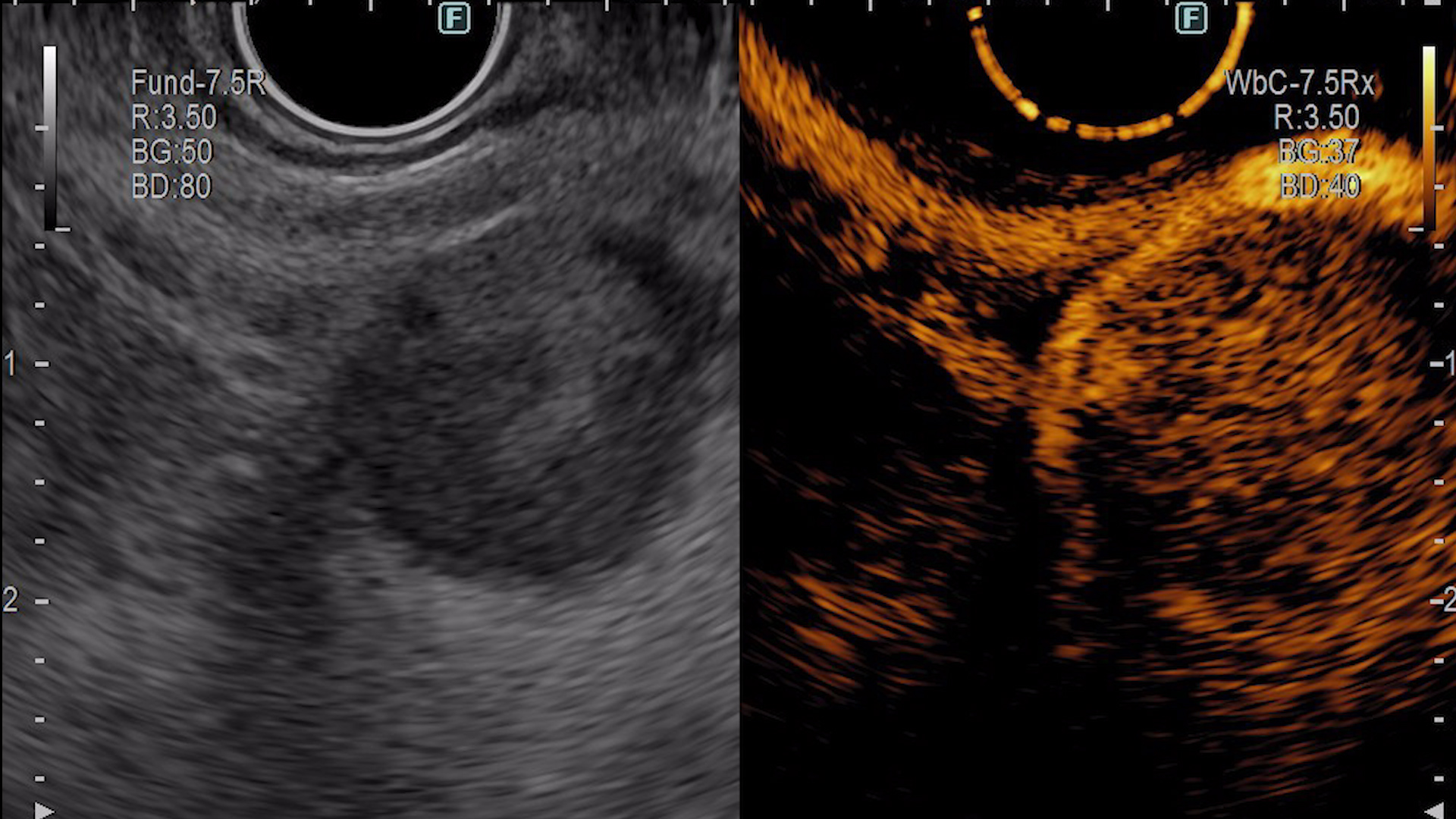

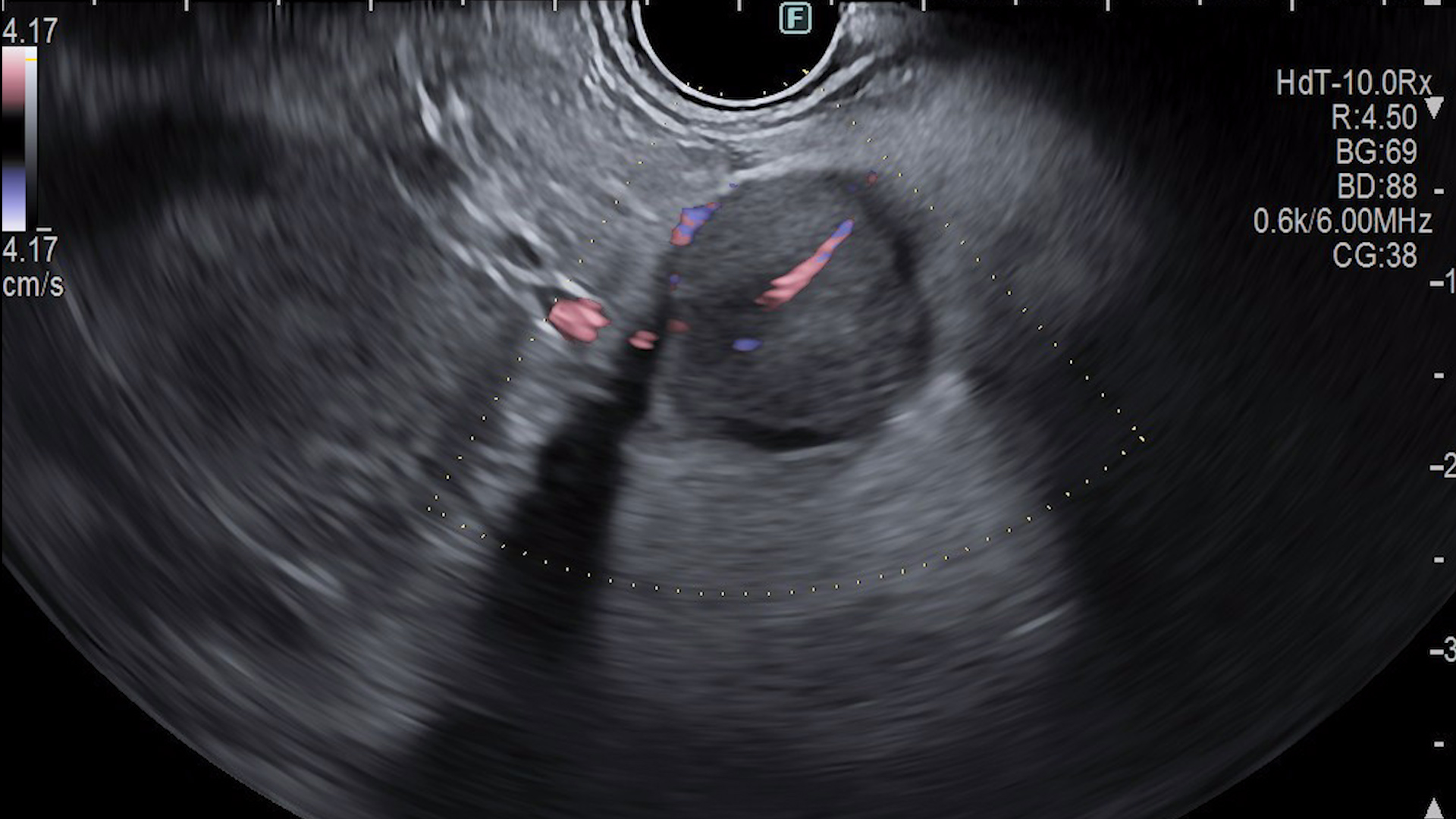

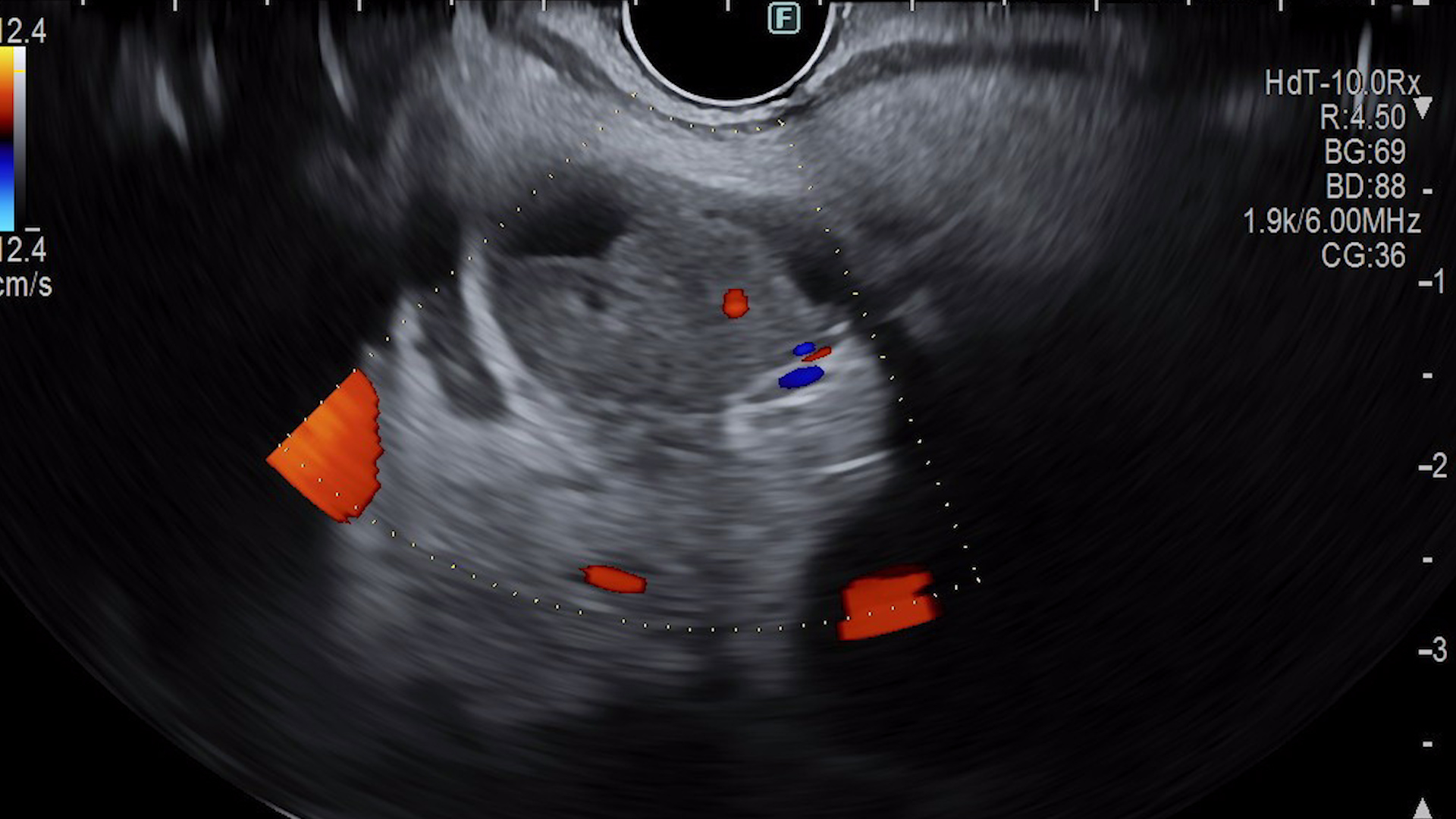

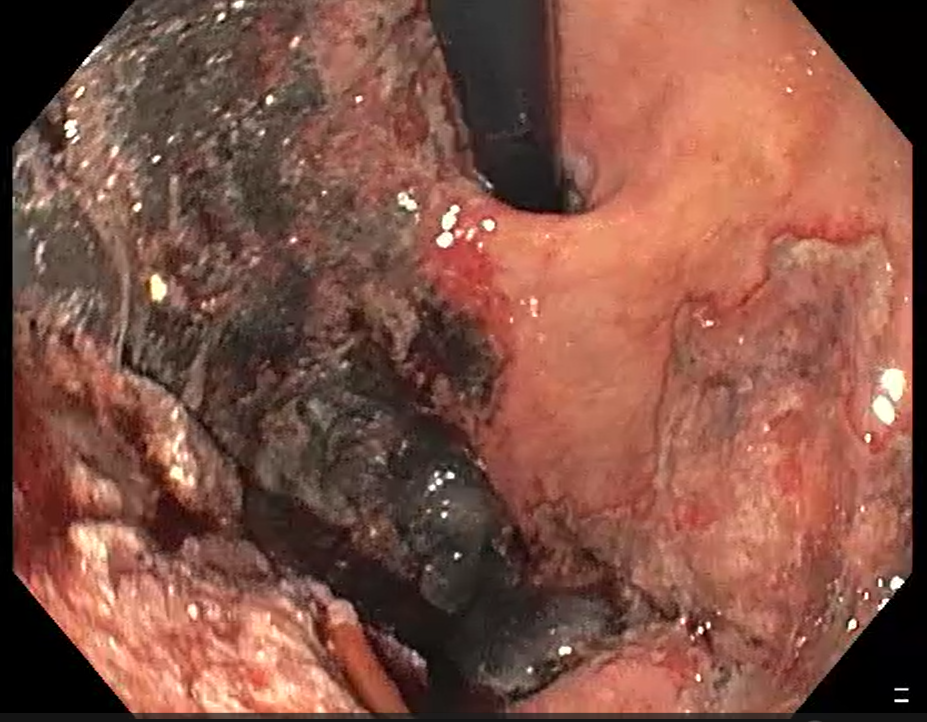

EUS: hypoechoic, relatively homogeneous, well-demarcated cephalo-pancreatic tumor, with regular margins, intensely vascularized, predominantly peripheral, with a basket pattern appearance on Doppler examination, with a nutrient vessel present. There is a cleavage plane between the formation and the neighboring structures. Mixed elastographic appearance with increased values.

When the contrast substance is administered, in the arterial phase, the tumor is hyperenhancing, with predominantly peripheral but also central contrast, with a relatively slow washout phenomenon in the venous phase. The appearance is suggestive of pancreatic metastases. Biopsy samples (FNB) are taken for histopathological analysis that classified the tumor as pancreatic metastasis with a renal cell carcinoma origin.

Pancreatic metastasis from a renal cell carcinoma.

Pancreatic tumors can be classified into: primary and secondary (especially from lung, breast, kidney, melanoma, gastrointestinal neoplasms). Pancreatic metastases are rarely encountered in medical practice (1). The CT examination is useful for the assessment of pancreatic lesions having its limits, very small tumors can go unnoticed. The MRI examination has greater sensitivity and specificity than CT examinations, being able to detect smaller pancreatic lesions (2).

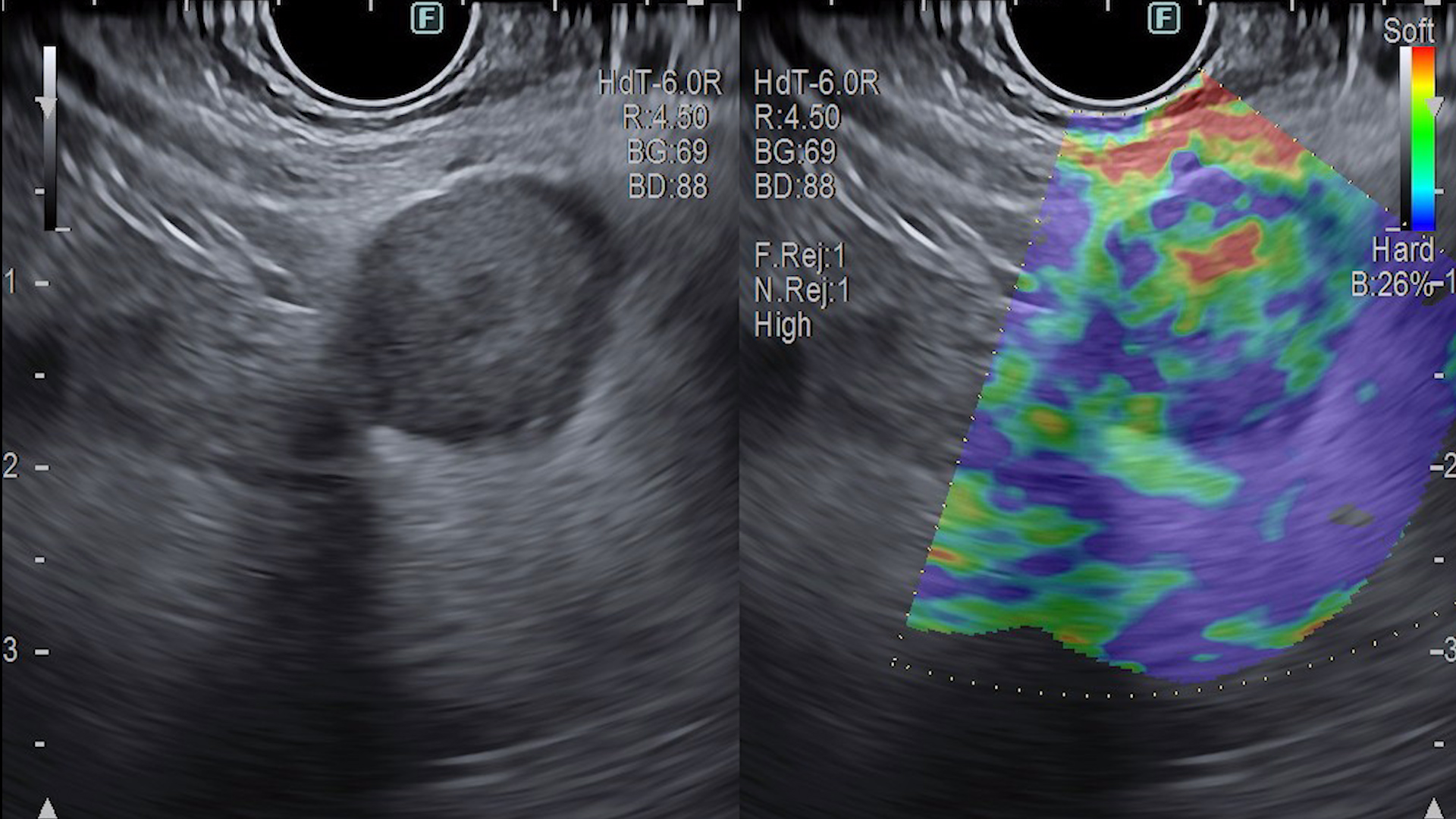

EUS is capable of detecting lesions smaller than 2 cm, lesions that may remain unnoticed during CT/MRI imaging evaluations and offers the possibility of FNA biopsies to obtain a definitive histopathological diagnosis. The echoendoscopic appearance can guide the diagnosis. Adenocarcinoma is often hypoechoic, poorly demarcated, with or without other malignancy criteria such as invasion into neighboring structures and locoregional adenopathy. Neuroendocrine tumors are hypoechoic, with margins well demarcated from the surrounding tissues, well vascularized. Most frequently, benign pancreatic formations appear heterogeneous, with calcifications. Pancreatic metastases are generally well defined, their appearance varies depending on the tumor of origin (Fig. 1, 2). (3-5)

In order to increase the accuracy of the differential diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, contrast enhanced- EUS can be performed, which allows the evaluation of the perfusion and uptake pattern of the lesion compared to the surrounding tissue. Thus, adenocarcinoma is described as hypoenhancing, NETs are hyperenhacing, and benign lesions are isoenhancing. Pancreatic metastases capture the contrast substance differently, depending on the tumor of origin: metastases of colonic, breast, and lung neoplasms are described as being hypoenhancing, while from kidney, melanomas and lymphomas are hyperenhancing (Fig. 3). Thus, EUS is useful in the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, especially for small tumors, and CEUS in their differential diagnosis. (2, 4). EUS elastography can also be used to increase diagnostic accuracy, as tumor tissue has a hard consistency, lower elasticity compared to normal or fibrous tissue (Fig. 4) (3)

In conclusion, the presented case highlights the importance of accurate investigations and advanced imaging technologies in the diagnosis of pancreatic lesions, especially secondary determinations. Contrast enhanced-EUS and EUS-guided biopsy (Fig. 5) played a crucial role in establishing the correct diagnosis in this case. Continued careful monitoring and evaluation of the patient’s progress is essential for appropriate treatment planning and optimal case management.

- Pancreatic tumors imaging: An update. Int J Surg. 2016 Apr;28 Suppl 1:S142-55. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.12.053. Epub 2016 Jan 9. PMID: 26777740. Scialpi M, Reginelli A, D’Andrea A, Gravante S, Falcone G, Baccari P, Manganaro L, Palumbo B, Cappabianca S.

- Imaging of the Pancreas. Ming-ming Xu, MD, Amrita Sethi, MD*. 2016.

- Endoscopic ultrasound of pancreatic tumors. Wangermez, M. s.l. : Elsevier, 2016.

- Yamashita Y, Kitano M. Endoscopic ultrasonography for pancreatic solid lesions. J Med Ultrason (2001). 2020 Jul and 31385143., 47(3):377-387. doi: 10.1007/s10396-019-00959-x. Epub 2019 Aug 6. PMID:.

- Sakamoto H, Kitano M, Kamata K, El-Masry M, Kudo M. Diagnosis of pancreatic tumors by endoscopic ultrasonography. World J Radiol. 2010 Apr 28;2(4):122-34. doi: 10.4329/wjr.v2.i4.122. PMID: 21160578; PMCID: PMC2999320.