See other cases

A Rare Cause of Severe Gastrointestinal Bleeding in an Elderly Patient

An 85-year-old male patient with a personal medical history of type II diabetes mellitus (diagnosed 20 years ago, treated with oral antidiabetic medication), duodenal ulcer (diagnosed 20 years ago), and ischemic stroke with sequelae. He was not under antiplatelet or anticoagulant therapy at home.

The patient presented with coffee-ground hematemesis that began en route to the hospital, along with progressive deterioration of general condition over the past week, and syncopal episodes at home. According to information obtained from family members, there had been no hematemesis, vomiting, or abdominal pain prior to this presentation.

His general condition was critical. He was conscious but uncooperative, responding minimally to verbal stimuli. He showed marked skin and mucosal pallor, and severely reduced subcutaneous tissue, suggesting a poor nutritional status. Blood pressure was 100/60 mmHg, heart rate 100 bpm, regular. He was afebrile. The abdomen was soft, non-tender on both spontaneous and palpatory examination. Rectal exam showed normally colored fecal matter. Upon insertion of a nasogastric tube in the emergency department, approximately 500 ml of partially digested blood was aspirated.

Laboratory tests revealed a severe normochromic normocytic anemia (Hb = 5.3 g/dl), a BUN/creatinine ratio >30, inflammatory syndrome, elevated lactate suggesting tissue hypoperfusion, and severe hypoproteinemia and hypoalbuminemia.

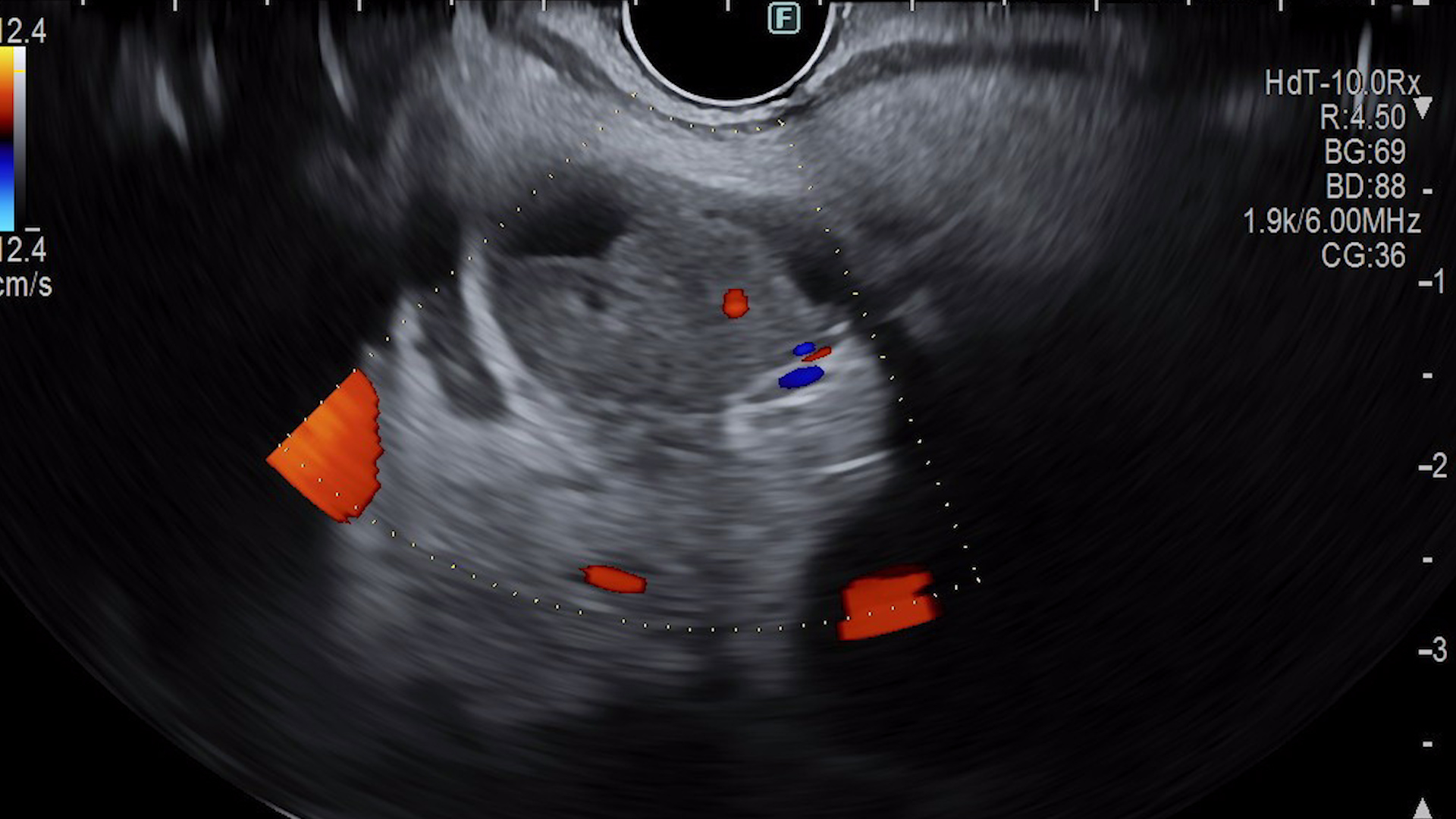

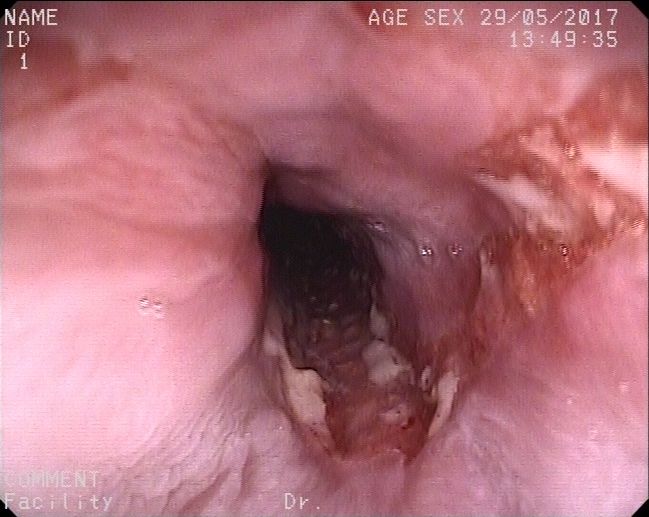

Upper gastrointestinal endoscopy (EGD):

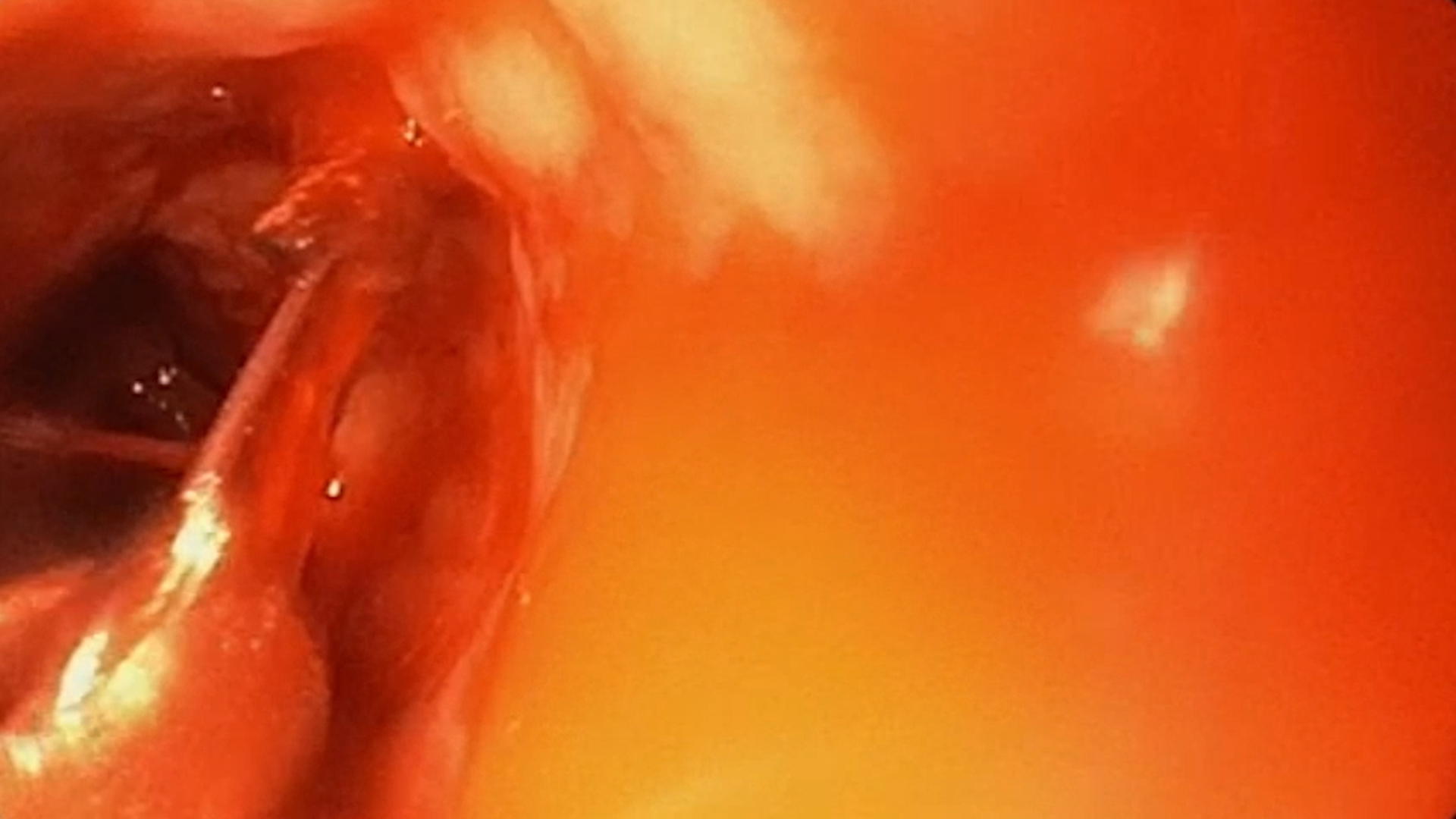

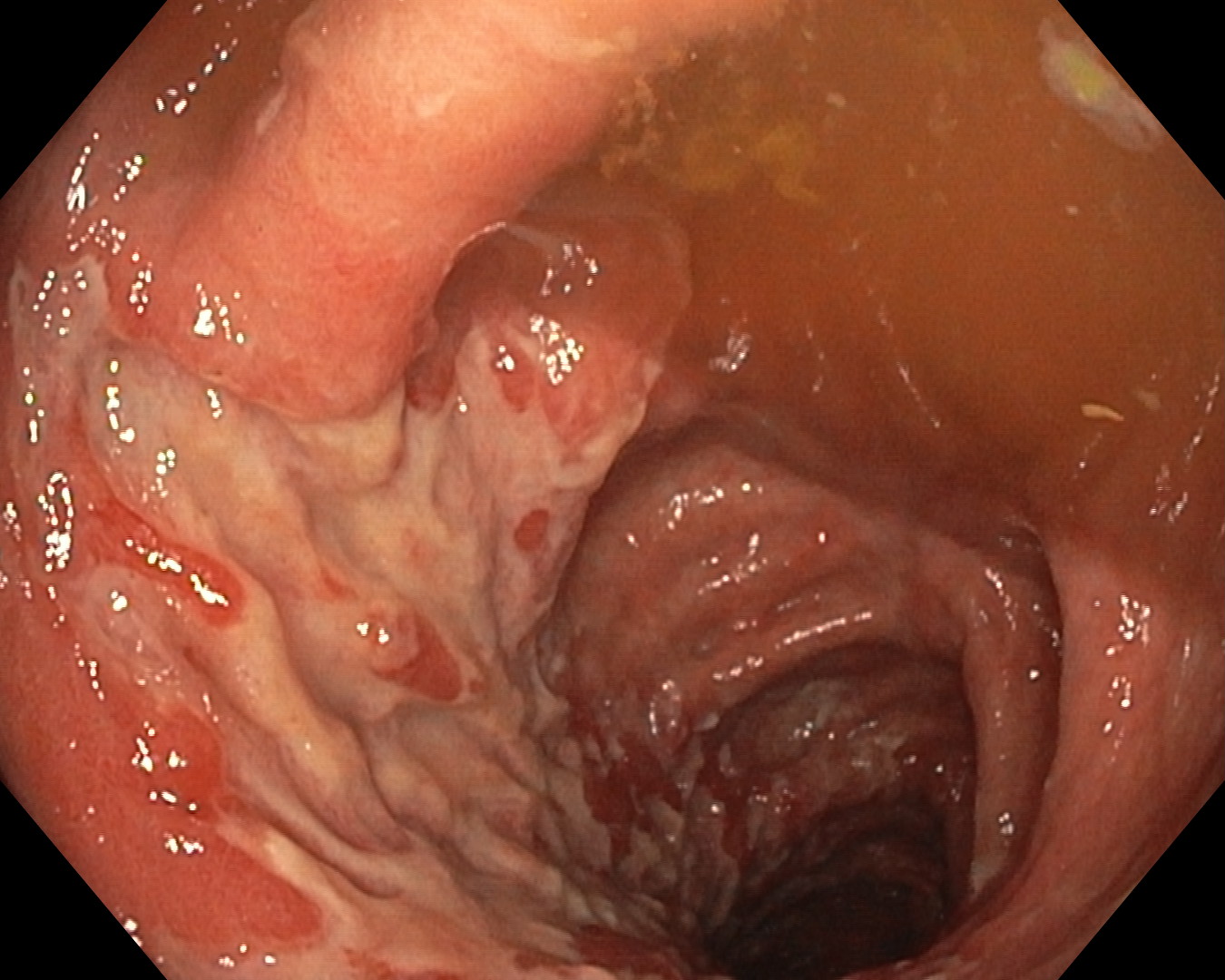

On introduction of the endoscope, no active bleeding source was initially observed in the esophagus, but the esophageal mucosa appeared necrotic. At the gastroesophageal junction, the mucosa was edematous, irregular, and appeared infiltrative. A moderate hiatal hernia was present. In the stomach, partially digested blood was noted and aspirated, with no active bleeding source identified. The body, fundus, and cardia (in U-turn view) appeared normal, as did the duodenal bulb and second portion of the duodenum.

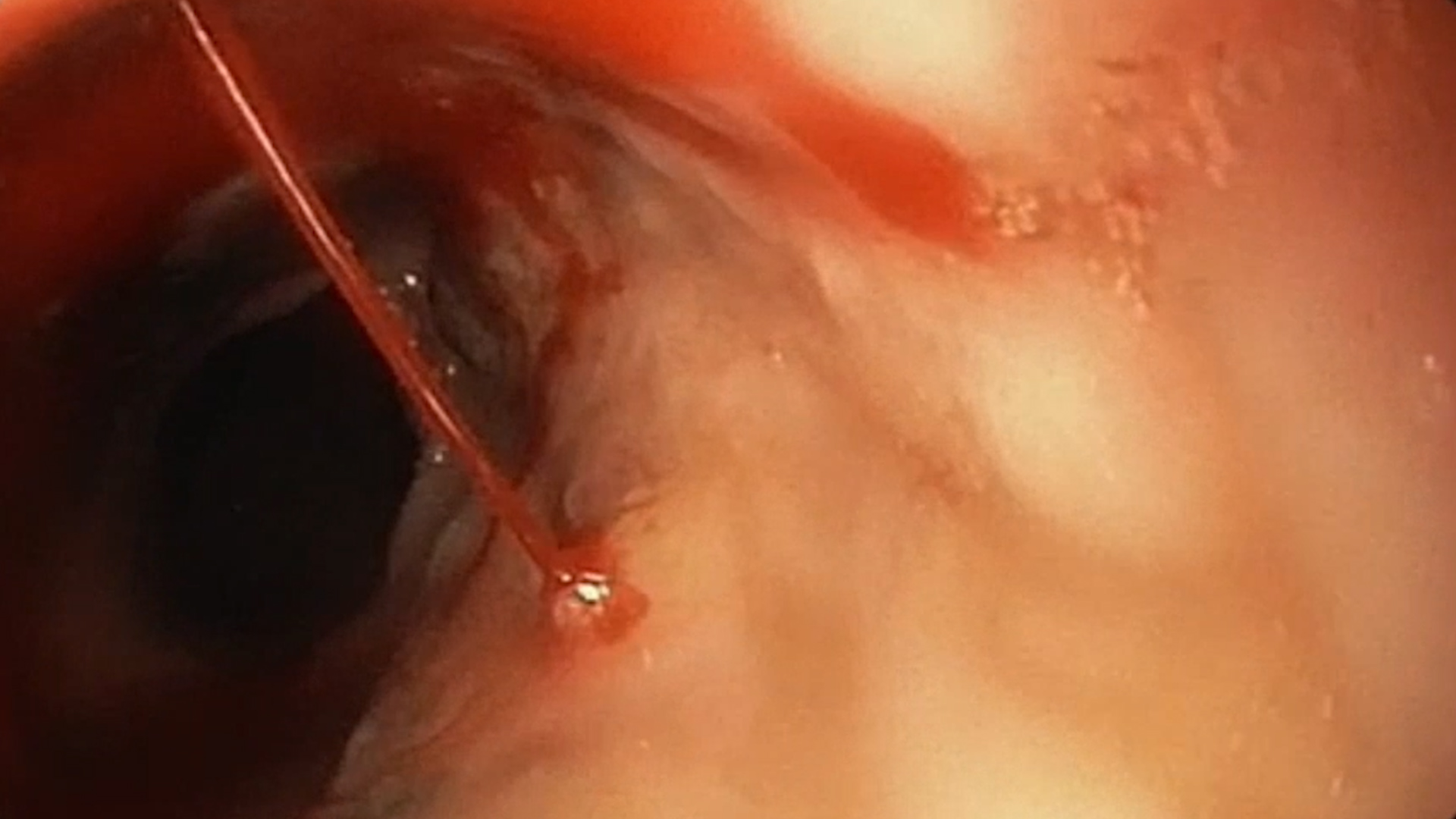

Upon withdrawal of the endoscope, necrotic areas alternating with normal mucosa, longitudinal erosions without ulcers, and an adherent clot were noted in the distal esophagus. The clot was removed by washing, which triggered active spurting bleeding from an esophageal artery. Attempted placement of a large hemostatic clip failed due to the stiffness of the surrounding tissue, causing the clip to slip. Adrenaline was injected in three perivascular points, which stopped the bleeding. Bipolar coagulation using a gold probe was also performed both on the vessel and adjacent high-risk areas, resulting in effective hemostasis. Although biopsy of the altered mucosa at the gastroesophageal junction would have been necessary, it was deferred due to the high risk of bleeding and the difficulty of achieving hemostasis.

- Necrotic esophagitis

- Active spurting upper gastrointestinal hemorrhage from an arterial vessel in the distal esophagus

- Effective endoscopic hemostasis using adrenaline injection and bipolar coagulation

Acute necrotic esophagitis (Black Esophagus) is a rare condition that predominantly affects elderly males with multiple comorbidities. The pathophysiological mechanisms include tissue hypoperfusion leading to ischemia, particularly in the distal esophagus, which is more poorly vascularized; damage to the mucosal protective barrier, often in the context of malnutrition and immunosuppression; and chemical injury from gastric contents affecting an already fragile esophageal mucosa.

In this case, advanced age, diabetes mellitus, malnutrition, and Candida glabrata sepsis were contributing factors. Differential diagnosis included severe reflux esophagitis, but the endoscopic appearance of necrosis without underlying ulceration, acute onset through upper GI bleeding, absence of typical GERD symptoms, presence of predisposing factors, and Candida glabrata infection favored the diagnosis of necrotic esophagitis.

Although endoscopic hemostasis was successful, the patient’s subsequent clinical course was complicated by fever, progressive inflammatory syndrome, dyspnea, and worsening general condition. Chest X-ray showed no areas of consolidation but revealed accentuation of the interstitial markings. Blood cultures were positive for Candida glabrata, confirming sepsis—an infection with a high mortality risk (20–60%).

- Necrotic esophagitis is a rare but potentially fatal cause of upper gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Risk factors include advanced age, diabetes mellitus, sepsis, malnutrition, and immunosuppression.

- Management includes endoscopic hemostasis, supportive care with fluid resuscitation, and targeted antibiotic or antifungal therapy in cases of associated infection.

- Gurvits GE. Black esophagus: Acute esophageal necrosis syndrome. World Journal of Gastroenterology. 2010, 16(26), 3219–3225.

- Săftoiu A; Cazacu S; Kruse A; Georgescu C; Comănescu V; Ciurea T. Acute esophageal necrosis associated with alcoholic hepatitis: is it black or is it white? Endoscopy. 2005, 37(3), 268–71.

- Pappas PG; Kauffman CA; Andes DR; Clancy CJ; Marr KA; Ostrosky-Zeichner L; Reboli AC; Schuster MG; Vazquez JA; Walsh TJ; Zaoutis TE; Sobel JD. Clinical Practice Guideline for the Management of Candidiasis: 2016 Update by the Infectious Diseases Society of America. Clinical Infectious Diseases. 2016, 62(4), e1–e50.